Before Rosa Parks, Claudette Colvin Took a Stand

Nine months before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat, a 15-year-old girl did it first

Nine months before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white woman, a 15-year-old girl did the same. She was a child who, like Parks, also grew up in rural Alabama. She dreamt of being a civil rights lawyer long before police dragged her off a public bus for civil disobedience. She was a child who, despite her act of protest, was ultimately deemed unsuitable to be the face of the bus boycott movement. But because of her actions on March 2, 1955, the world was deeply changed, kicking off a series of events that helped bring segregation to its knees.

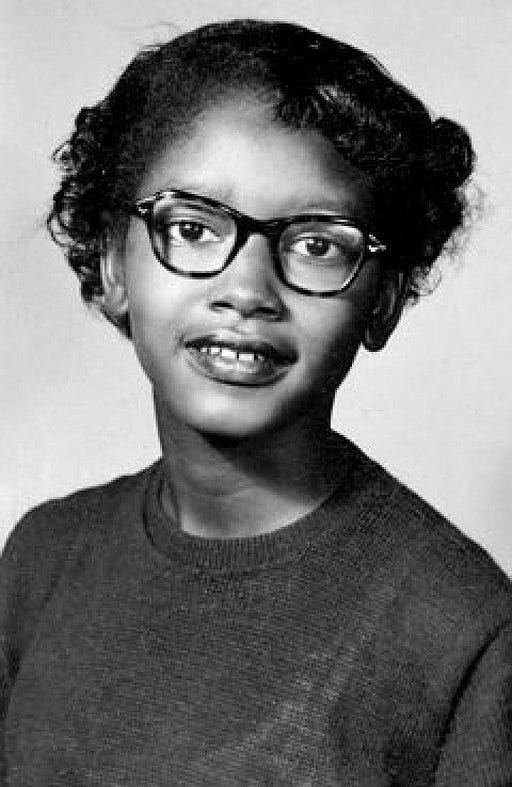

Who is Claudette Colvin?

Claudette Colvin was born on September 5, 1939, in Birmingham, Alabama. At first, Colvin and her sister were raised by their aunt and uncle on a farm in Pine Level, Alabama. Rural life couldn’t shield her from the dehumanization of racism. In an interview with The Guardian, Claudette recalls white children taunting her skin during trips to the general store, demanding to see her hands and touching them, like she was less of a human and more of a science experiment. She also recalls the anger from the white children’s parents, appalled and disgusted that their children had touched a Black person.

In 1952, after her sister died from polio, Claudette moved to Montgomery, Alabama, and started high school at Booker T. Washington, a segregated school for African Americans.

The violence of racism grew more imminent around her, as it often does as young children become teenagers. Claudette had a 16-year-old neighbor named Jeremiah Reeves who also went to Booker T. Washington High School. He played in a local jazz band and worked as a grocery delivery boy.

One day, Reeves was accused of raping a white woman. Claudette Colvin witnessed his arrest.

He was tortured by police, placed in an electric chair and told that if he did not confess, he would be electrocuted. In fact, the police said to him that if he did not confess to raping all of the local white women who had been raped that summer, he would die. He confessed.

Later, Reeves retracted the confession, saying that it was coerced.

But in a two-day trial in which the jury deliberated for less than half an hour, Reeves was sentenced to death. The NAACP and one of its star lawyers, Thurgood Marshall (who later became the first Black justice on the Supreme Court), rallied to Reeves’ defense, and so did Black activists and community members from across Alabama.

A local leader, Reverend. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., joined the effort, helping highlight the larger injustices at play—like oftentimes, cases in which Black women were raped were never investigated.

The case captured Claudette Colvin’s attention, it was close to home. One day, her teacher asked her class to write an essay in response to the question, “How Do I Feel as an American?” Such a question stunned her, as she recalls, “We wasn’t considered Americans…we was considered negroes. And we was treated by the ruling class as second-class citizens.”

She wrote her essay about Jeremiah Reeves.

Protesting segregation on a city bus

Colvin was inspired not only by the injustices she witnessed but also by her education—learning about Black resistance movements worldwide, like the Mau Mau Rebellion in Kenya, the work of Black poets like Paul Laurence Dunbar, and playwrights like William Shakespeare. Colvin was also a member of the local NAACP Youth Council, where she learned more about activism and organizing.

All of these experiences moved her to put her pain and dismay into action.

After school on March 2, 1955, while Jeremiah Reeves was still on death row, Claudette Colvin and her friends boarded a public bus in Montgomery, Alabama. She sat down in her seat and looked through her window as, gradually, more passengers arrived, and the white section of the bus filled up. The bus driver yelled at Colvin and her friends, demanding that they give up her seat for a white woman who was standing. She said no.

Recalling how she felt in that moment, Colvin told The Guardian, “History had me glued to the seat…it felt as if Harriet Tubman’s hand was pushing me down on the one shoulder, and Sojourner Truth’s hand was pushing me down on the other.”

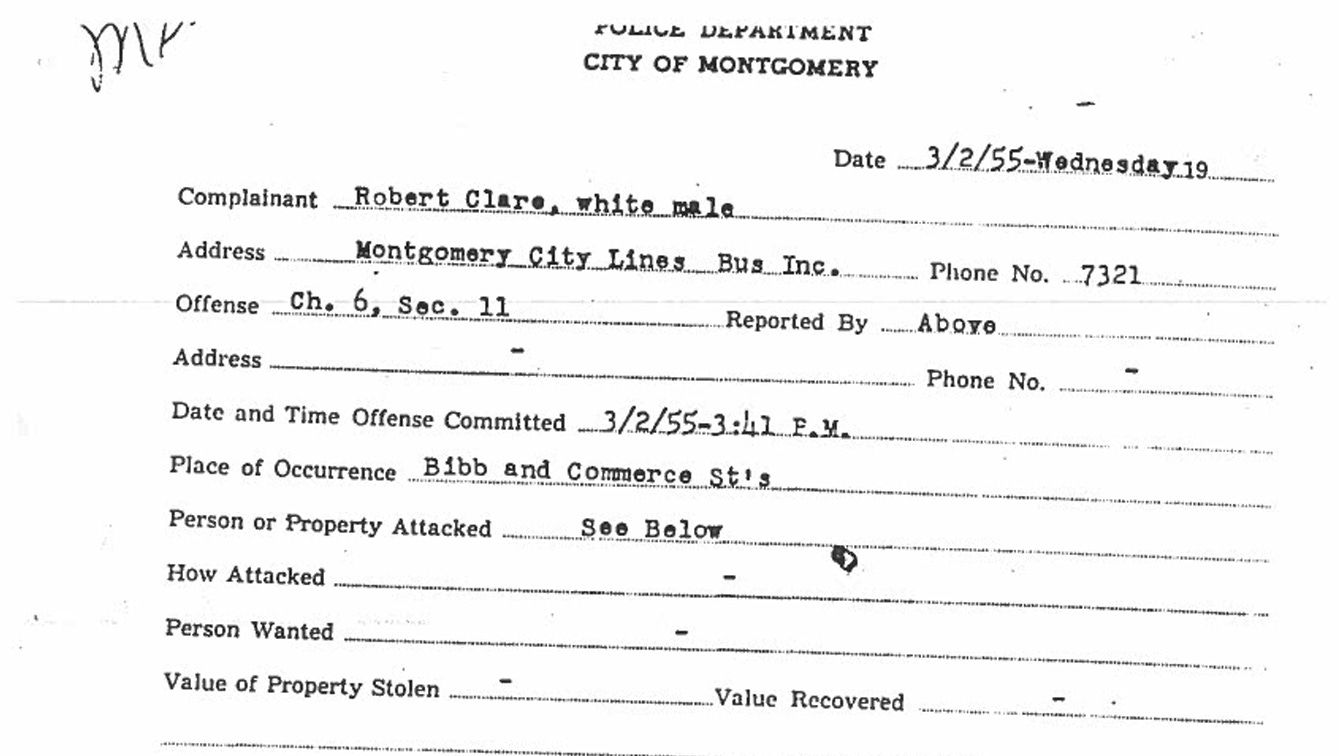

The following is an excerpt of an official report from Montgomery police department, taken the day Colvin was arrested.“When we arrived there we were informed by the driver of the Highland Gardens Bus that there were two colored females sitting opposite two white females…”

“...an unidentified colored female was sitting in this disputed seat moved to the rear when we asked her to; but Claudette Colvin, aged 15, colored female, refused.”

Colvin told the officers that she knew her rights.

They dragged her off the bus and as she recalls, her body went limp. The officer arrested her and in the police car, made lewd comments about her body and physical appearance, to the point that she feared sexual violence.

The police officer wrote in their official report that she was not peaceful, “We then informed Claudette that she was under arrest. She struggled off the bus and all the way to the police car. After we got her in the police car she kicked and scratch[ed] me on the hand and also kicked me in the stomach.”

Who gets to be the face of the bus boycott movement?

As she awaited trial, local civil rights activists began to organize and discuss how they could challenge the case. Rosa Parks, who had not yet performed her own famous act of protest, was a secretary for the NAACP and a seamstress. The two had known each other from the NAACP Youth Council. Parks helped fundraise for Colvin and aided in the local organizing efforts.

Colvin’s case went to trial a few months later. At first, she faced three charges: disturbing the peace, breaking segregation law, and assaulting an officer. The first two charges were dropped. She was found guilty of the third charge.

This presented an obstacle for local activists. To them, it would only make sense to appeal Colvin’s conviction if she was found guilty of violating segregation laws because these were the laws that they wanted to prove were immoral and illegitimate. But resisting arrest was not a segregation law.

This was one of the reasons why Colvin was deemed an unsuitable candidate to be the movement’s public face for a bus boycott. Additionally, more sinister factors contributed to her being ostracized. Some said her skin was too dark to be the face of the boycott, some said too young. And then there was the fact that she’d become pregnant after the conviction although she was not married, which was considered taboo at the time. They needed a nearly perfect poster-person, someone who couldn’t easily be picked apart by the opposition, they reasoned. Colvin had too much baggage.

So local activists kept looking.

Claudette Colvin’s lasting impact:

On December 1, 1955, nine months after Claudette Colvin’s arrest, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. What followed was a remarkable 13-month bus boycott and protest. This led to a Supreme Court case, Browder vs. Gayle, establishing that such segregation was unconstitutional. Claudette Colvin was a plaintiff in this landmark case.

Colvin was abandoned by local activists, and because of that, demoralized. She gave up on her dreams to be a civil rights lawyer.

As a young adult, she moved to New York and became a nursing assistant.

In 2021, when Colvin was 82 years old, her court record was officially wiped clean by a judge.

Epilogue:

A follow-up on Jeremiah Reeves. He was executed by the state of Alabama on March 28, 1958. He was 22 years old at the time of his death.

Here is part of Reverend. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s speech about Jeremiah Reeves, in the aftermath of his execution:

“It is regrettable but true that in almost any session of our city, county and state courts one can see all of the injustices which the prophet Amos so bitterly decried and which he predicted would mean the ruin of their once glorious civilization. Here Negroes are robbed openly with little hope of redress. We are fined and jailed often in defiance of law. Right or wrong, a Negro’s word has little weight against a white opponent’s. And if the Negro insists on the right of his cause, as opposed to a white man’s he is often violently treated.

There is another injustice in the courts which is equally as bad. Cases in which only Negroes are involved are handled frivolously, without regard to justice or proper correction. We deplore this type of injustice as much as we do the injustice which the Negro confronts in his court relations with whites.

We appeal this afternoon to our white brothers, whether they are private citizens or public officials, to courageously meet this problem. This is not a political issue: it is ultimately a moral issue. It is a question of the dignity of man.

In the name of God, in the interest of human dignity and for the interest of human dignity and for the cause of democracy, we appeal to these thousands to gird their courage, to speak out and act on their basic convictions.”

This speech was given on Easter Sunday, April 6, 1958, on the steps of the state capitol of Alabama.

Author’s note:

Happy Black History Month! Thank you for taking the time to read the story of Claudette Colvin. Imagine only being 15-years-old and taking a stand like this. And imagine, later on, seeing the country overlook your contributions to such a monumental movement.

It's a reminder that movements are multifaceted and so many people sacrificed to make them successful.

Please share this story with family and friends, or whoever you think would be interested in it!

Remember to subscribe to this free newsletter, where you can find other stories about positivity, connection, and ingenuity!

And if you have a historic figure, event, or any general idea you'd like me to cover, please email contact@become-all.com or leave a comment here.

Thank you!

— Cynthia Betubiza